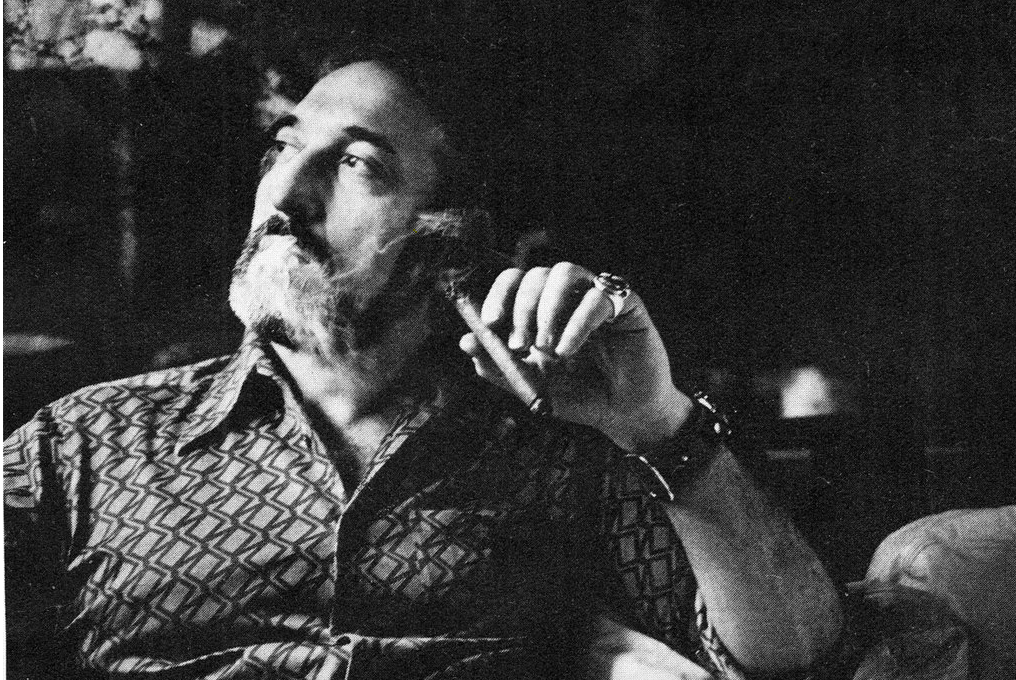

Bruce Jay Friedman: An Interview

During his five-decade writing career, Bruce Friedman published eight novels, four story collections, numerous plays, and such screenplays as Stir Crazy (1980) and Splash (1984), for which he was nominated for Best Original Screenplay.

On June 3, 2020, he passed away at the age of 90.

In 2009, I interviewed him for my book And Here’s the Kicker. The interview, cut for space by the publisher, was later included in my 2014 book of interviews, Poking a Dead Frog.

Though he never became a household name, Friedman has many famous admirers and friends. The Godfather author Mario Puzo once described Friedman’s stories as being “like a Twilight Zone with Charles Chaplin.” Neil Simon adapted Friedman’s short story “A Change of Plan” (originally published in Esquire magazine) into a 1972 movie blockbuster, The Heartbreak Kid, directed by Elaine May and starring Charles Grodin and May’s daughter, Jeannie Berlin.

Steve Martin, who turned Friedman’s semi-autobiographical book The Lonely Guy (1978) into a feature film in 1984, provided a back-cover blurb for Friedman’s story collection, Even the Rhinos Were Nymphos (2000), that perfectly, if sarcastically, summarized the sentiments of so many of his contemporaries and would-be imitators: “I am not jealous.” (Gordon Lish, the well-respected publisher of, among others, Raymond Carver, Richard Ford, and Don DeLillo, is also blurbed on the back-cover: “Bruce Jay Friedman is an American original whose least engaged considerations can beat the crap out of almost anything else on this block.”)

In 1962, while working full-time as an editor of various men’s magazines, Friedman published his first novel, Stern, which is widely considered to be his masterpiece. The book, which Friedman wrote in a mere six months, when he was in his early thirties, tells the story of a man who leaves the city for the suburbs, only to discover his new home is far from the tranquil residential development of his imagination. He’s attacked by neigborhood dogs. He develops an ulcer. His family is harassed by an anti-Semite, who, during one altercation, pushes Stern’s wife to the ground. The reader never learns his first name.

Born in the Bronx in 1930, Friedman’s initial ambition was to become a doctor—at first. Switching gears, he ultimately decided to earn a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Missouri. But his true literary education came while serving as a first lieutenant in the United States Air Force, from 1951 and 1953. According to Friedman, his commanding officer suggested he read three novels: Thomas Wolfe’s Of Time and the River, James Jones’s From Here to Eternity, and J.D. Salinger’s Catcher in the Rye. After consuming these novels in a single weekend, Friedman realized that he wanted to attempt to write fiction for a living.

Along with Kurt Vonnegut, Friedman is often credited as being one of the pioneers of “dark comedy.” In 2011, Dwight Garner, of the New York Times, wrote that Friedman’s The Lonely Guy’s Book of Life “makes low-level depression and ineptitude seem stylish and ironic, almost a supreme way of being in the world.” From plays like “Steambath” (1970), in which it’s revealed that a Puerto Rican steam-room attendant is God, to short stories, such as 1963’s “When You’re Excused, You’re Excused,” in which the main character tries to convince his wife to let him skip Yom Kippur to work out at the gym, Friedman’s take on humanity is almost always bleak, but always amusingly realistic.

In his foreword to Black Humor, an anthology he edited in 1965, Friedman argued that the thirteen writers presented in the collection weren’t just “brooding and sulking sorts” determined to find levity in the world’s misery. Rather, they were “discover[ing] new land” by “sailing into darker waters somewhere out beyond satire.” Not surprisingly, the very same sentiment could be used to describe Bruce Jay Friedman.

What follows is the original length interview I conducted with Mr. Friedman.

I’ve read that you don’t like to be known as a humorist.

I don’t, especially. James Thurber, Robert Benchley, S. J. Perelman—they are the great humorists. They set out to make you laugh. That’s never my intention, although it’s often the result. As a writer, I couldn’t possibly be more serious. Sometimes the work is expressed comedically. The hope is that it’s unforced and doesn’t seem worked on, which, of course, it is.

So you agree with Joseph Heller that humor isn’t the goal, per se, but the means to the goal?

I’m not comfortable with the idea of “using” humor to achieve a purpose. I can’t imagine Evelyn Waugh, while writing [the 1928 satiric novel] Decline and Fall, saying, “I think I’ll use a little humor here.” But there’s a theory that a writer can’t make a claim to greatness unless there’s a streak of comedy in his work. There may be some truth to that.

I’m not much good at jokes, can’t remember them. However, once upon a time, I volunteered to be the master of ceremonies at a sorority event at the University of Missouri, which I attended in the late forties and early fifties. The mic went dead after about six jokes, all of which were borrowed from a Borscht Belt comedian. One was, “I don’t have to be doing this for a living, folks. I could be selling bagels to midgets for toilet seats.” The room was filled with gorgeous women who began to talk among themselves and to cross and uncross their legs.

I became rattled and shouted out, “Will you please quiet down? Don’t you see I’m trying to be funny here?” I then fainted. Someone named Roth helped revive me. “What did you have to faint for?” he asked. “You were terrific.”

In l965, you put together Black Humor, a collection of short stories featuring such writers as Thomas Pynchon, Terry Southern, John Barth, and Vladimir Nabokov. In the foreword, you coined and popularized the term “black humor.” You’ve since said that you feel somewhat stuck with that term.

I do. I hear it all the time, and it makes me wince. Essentially, it was a chance for me to pick up some money—not that much, actually—and to read some writers whose work was new to me.

In retrospect, a more accurate term would have been tense comedy—there’s much to laugh at on the surface, but with streaks of agony running beneath. I had no idea the term black humor would catch fire to the extent that it did—and last this many years. The academics, starving for a new category, wolfed it down.

What similarities did you notice among these “black humorist” writers’ works?

Each one had a different signature, but the tone generally was much darker than what was found in most popular fiction at the time. There was a thin line between reality and the fantastical. Their works featured ill-fated heroes. It also confronted—perhaps not consciously—social issues that hadn’t been touched on. Pressed to the wall, I’ll use a term that’s sickeningly in vogue today: It was edgy.

Why do you think the term “black humor” became so popular, so quickly?

It’s catchy, and that’s appealing to publishers, critics, academics. Some of it may have had to do with the political and social climate of the mid-sixties. The drugs, the Pill, the music, the war—comedy had to find some new terrain with which to deal with all of this. I imagine each generation feels the same.

After the book was published in l965, my publisher threw a huge “Black Humor” party—I still have the invitation—and the whole world showed up. I recall Mike Nichols and Elaine May having a high old time. The “black humor” label started to get reprinted and quoted after that party, and it never stopped. Ridiculous.

When did you begin writing your first novel, Stern?

In l960; it took about six months. I had been trying to write another book for three or four years but it never came together. Certain notions aren’t born to be novels. I figured that out—at great expense. I wrote Stern on the subway and train to and from work. I wrote it in a heat, like I was being chased down an alley.

Stern seems like a break from the type of books that came before it. It seems more ethnic; more psychoanalytic. The main character is an anxiety-ridden Jewish nebbish who feels taken advantage of by his Gentile suburban neighbor. The book was very influential for a lot of writers, including Joseph Heller, Nora Ephron, Philip Roth, and, later, John Kennedy Toole, the author of A Confederacy of Dunces. When you were working on it, did you feel as if you were working on something new?

I was simply trying to write a good book—and an honest one—after struggling with a book that kept falling apart. I was living in the suburbs and feeling isolated, cut off from the city. I constructed a small and painful event, and I wrote a novel around it—a man’s wife falls to the ground, without any underwear, and is seen by an anti-Semitic neighbor. I hoped the book would be published and that afterward I wouldn’t be run out of the country. I’m quite serious. I thought I’d hide in Paris until it all blew over. Such ego. It’s not as if I had a dozen book ideas to choose from. Stern was the one I had—the story felt compelling—and that’s the one I wrote.

This main character was not your typical macho, male literary hero; he was fearful about many things, including sex.

I certainly had that side at the time. All writing is autobiographical, in my view, including scientific papers.

Stern was a book that was in direct contrast to the short stories I had written up to that time. I’m told that it was a departure from much of the era’s fiction. The New Yorker literary critic Stanley Edgar Hyman called it “the first true Freudian novel.” It only sold six thousand copies. The editor, Robert Gottlieb, who edited Catch-22, which was published just before Stern, told me that they were the “right copies.” I remember wondering what it would have been like if it sold a hundred thousand wrong copies.

The only book that had a distant echo was Richard Yates’s Revolutionary Road. And, of course, John Cheever’s stories, which touched on suburban alienation in New England.

Do you think Stern influenced Revolutionary Road, which was written around the same time?

I doubt it, but I do know that Yates was aware of it. I knew Yates when I was working as an editor in the fifties and sixties, at the Magazine Management Co., which published men’s adventure magazines. He just showed up without explanation for a few weeks, this man with a handsome and ruined, disheveled look, and attached himself to our little group—and then he disappeared. From time to time he’d call me from the Midwest to ask if I could get him a job. It annoyed me that he thought of me as a publisher or producer. Never once did he acknowledge that I was a writer. But I later learned that Stern was one of the few novels that he taught in his writing classes.

Yates had a difficult life. He was a major alcoholic, and he always struggled for money. In other words, your basic serious novelist.

It’s a shame that Yates’s life was so difficult. He was a brilliant writer, and a very funny one.

I agree. He was a gifted man—his writing was pitch-perfect—but he probably had a demon or two more than the rest of us. He’d complain that if Catch-22 hadn’t been such a big hit, Revolutionary Road would have been a bestseller.

There was an incident in which a few writers and editors, including myself, went out for a drink in the early seventies, and Yates joined us. He drank so much that he collapsed and fell forward, hitting his head on the table. My secretary at the time, who hadn’t paid much attention to him, pulled him to his feet, and off they went together. I never saw either of them again. They ended up living together.

Tell me about your experience editing adventure magazines in the 1950s and ’60s for the Magazine Management Co. What were some of the publications under the company’s umbrella?

There were more than a hundred, in every category—movies, adventure, confession, paperback books, Stan Lee’s comic books. Stan worked there for years and years. The office was located on Madison Avenue in Midtown Manhattan. I was responsible for about five magazines. One was called Focus—it was a smaller version of People, before that magazine was even published.

I also worked as editor of Swank. Every now and then the publisher, Martin Goodman, would appear at my office door and say, “I am throwing you another magazine.” Some others that were “thrown” at me included Male, Men, Man’s World, and True Action.

Swank was not the pornographic magazine we know today, I assume?

Entirely different, and I don’t say that with pride. Mr. Goodman—his own brother called him “Mr. Goodman”—told me to publish a “takeoff” on Esquire. This was difficult. I had a staff of one, the magazine was published on cheap paper, and it contained dozens of ads for automotive equipment and trusses, which are medical devices for hernia patients.

When I was there, it wasn’t even softcore porn; it was flabby porn. There was no nudity, God forbid, but there were some pictures of women wearing bathing suits—not even bikinis—and winking. There were also stories from the trunk—deep in the trunk—from literary luminaries such as [novelist and playwright] William Saroyan and Graham Greene and Erskine Caldwell [author of the novel Tobacco Road]. When sales lagged, Mr. Goodman instructed me to “throw ’em a few ‘hot’ words.” “Nympho” was one that was considered to be arousing. Dark triangle would be put into play when the magazine was in desperate straits. We once used it in an article called “The Rock-Around Dolls of New Orleans.”

In doing research for this interview, I read issues of those magazines and found many of the articles to be incredibly funny and entertaining.*

We tried to keep to a high standard, within the limits of our pathetic budget. Some awfully good writers passed through the company. The adventure magazines had huge circulations and were mostly geared to blue-collar types, war veterans, young men—up to one million readers, with no paid subscribers. But their popularity faded when World War II vets grew older and more explicit magazines became readily available. The only reader I’ve ever actually met in person is my brother-in-law.

* A sampling of 1950s and ’60s men’s magazine article headlines: “Fearsome Fangs Tore My Flesh”; “Some Dames are Murder”; “Kicked to Hell by Mad Horses”; “Back Alley Kicks of the Teen Sex Cults”; “Soft Flesh for the Nazi Monster’s Pit in Hell”; “The Virgin Groom: A Young Bride’s Worst Enemy”; “Serenade to a Nude Wood Nymph”; “Why Women Write Hot Diaries”; “Birth Control Gadgets That Kill”; “Radiation—and the Freaks of Tomorrow”; “The Passionate Virgin No Cage Could Hold”; “Satan’s Pigs Ate Us Alive”; “Motels: Hideouts for Hidden Sin”; “His Head Was a Flaming Torch”; “Weasels Ripped My Flesh” [later used as the title for the 1970 Frank Zappa album]; “Nudism Exposed”; “I Saw Sex Drugs Work”; “New U.S. Terror: Hoods with Switchblade Knives”; “Milwaukee: Dames, Dice and Dope”; “Weird Obsession for Women’s Teeth”; “A Pfc’s Hilarious Ordeal: The Orgy That Won Me a Silver Star”; “A Report on the Love-Happy Housewives of Suburbia: Nymphos with a Ranch House”; “Are Nymphomaniacs Normal?”; “The Nympho Fuehrer of Nazi Island”; “Eaten Alive on a Bed of Gold”; “She’s Young, She’s Lovely, She’s French All Over”; “The 16 Wives of Ben the Hermit”; “Ram the Periscope and Hang On!”; “Skull Hunt on Pygmy Island”; “The True Facts About America’s Trailer Camps”; “Kick-Crazy Co-Ed Call Girls”; “Wife Swapping—Our New National Pastime”; “I Was a Sex Maniac: A Public Interest Story”; “Revealed: The Lesbian Explosion and What It Means to You”; “Dance, My Darlings, to the Whip’s Evil Song!”; “Lay Off the Sinatra Jokes Or I’ll Kill You”; “My Fists Drew Blood When I Caught Him with My Faithless Jungle Woman!” —From It’s a Man’s World, edited by Adam Parfrey, Feral House, 2003.

Were these types of magazines called armpit slicks?

Only by the competition. They were also called jockstrap magazines.

Believe it or not, there was a lot of status involved. True magazine considered itself the Oxford University Press of the group and sniffed at us. We, in turn, sniffed at magazines we felt were shoddier than ours. There was a lot of sniffing going on.

We published a variety of story types. People being nibbled to death by animals was one type: “I Battled a Giant Otter.” There was no explanation as to why these stories fascinated readers for many years.

“Scratch the surface” stories were also a favorite. These were tales about a sleepy little town where citizens innocently go about their business—girls eating ice cream, boys delivering newspapers—but “scratch the surface” of one of these towns and you’d find a sin pit, a cauldron of vice and general naughtiness.

The revenge theme was popular, as well—a soldier treated poorly in a prison camp, who would set out to track down his abuser when the war ended. And stories about G.I.s stranded on Pacific islands were a hit among veterans—especially if the islands were populated by nymphos. “G.I. King of Nympho Island” was one title, I recall.

Sounds convincing.

Mr. Goodman always asked the same question when we showed him a story: “Is it true?” My answer was, “Sort of.” He’d take a puff of a thin cigar and walk off, apparently satisfied. He was a decent, but frightening man.

Walter Kaylin, a favorite contributor, did a hugely popular story about a G.I. who is stranded on an island and becomes its ruler. The G.I. is carried about on the shoulders of a little man who has washed ashore with him. There wasn’t a nympho on the island, but it worked.

Who, by and large, wrote for these magazines?

Gifted, half-broken people—and I was one of them—who didn’t qualify for jobs at Time-Life or at the Hearst company. I don’t think of them as being hired, so much as having just ended up there. In terms of ability, I would match them against anyone who worked in publishing at the time. We just didn’t look like the cover models for GQ.

Walter Wager was a contributor, and he went on to write more than twenty-five suspense novels, including, under a pseudonym, the I Spy series. He had a prosthetic hand that he would unscrew and toss on my desk when he delivered a new story. Ernest Tidyman worked for the company; he wrote the Shaft books and the first two movies. Also, the screenplay for The French Connection.

In the early sixties, I was editing Swank when Leicester Hemingway—pronounced “Lester”—came barreling into my office. He was Ernest’s brother, and he looked more like Ernest than Ernest himself. He called Ernest “Ernesto.” He was bluff and cheerful and handsome in the Clark Gable mold. He had gotten off a fishing boat that very day and wanted me to publish one of his stories. How could I say no? This was as close as I’d ever get to the master.

He left. I read the story. The first line was “Hi, ho, me hearties.” It was totally out of sync with what we were doing, and it was unreadable. I remember it being called “Avast.” So, I was in the position of having to turn down Ernest Hemingway’s brother.

A few years later, I went to a party given by George Plimpton, and I met Mary Hemingway, the last of Ernest’s four wives. I told her that I’d had the nicest meeting with Leicester. “What a wonderful man he is.”

“That swine!” she said. “How dare you mention his name in my presence!”

Apparently, this highly decent man was considered the black sheep of the family—at least by Mary. And that’s really saying something.

How many stories did you have to purchase for all of your magazines in a typical month?

Fifty or sixty.

Per month?!

Yes. I was an incredibly fast reader—a human scanner. My train commute to work took more than two hours each way, a total of close to five hours. I got a lot of work done on that train—much more than I do now with a whole day free and clear. I wrote most of Stern on that train.

My best move at this job was to hire Mario Puzo, later the author of The Godfather. The candidates for the writing job got winnowed down to Puzo and Arthur Kretchmer, who later became the decades-long editorial director of Playboy. I knew how good Kretchmer was, but I needed someone who could write tons of stories from Day One, so I hired Puzo in 1960 at the princely salary of $l50 a week. But there was an opportunity to dash off as many freelance stories as he wanted, thereby boosting his income considerably. He referred to this experience as his first “straight” job. When I called him at home to deliver the news, he kept saying in disbelief, “You mean it? You really mean it?”

Was Puzo capable of writing humor?

He was concerned about it. Now and then, at the height of his fame and prominence and commercial success, he would look off wistfully and ask, “How come Hollywood never calls me for comedy?”

There is some grisly humor in The Godfather. As for setting out consciously to write a funny book—I’m not sure. At the magazines, one of the perks as editor was that I got to choose the cartoons. There was an old cartoon agent, a real old Broadway type who stuttered. He would come stuttering into the office carrying a batch of cartoons, each of which had been rejected eight times already.

Mario insisted he could have done a better job of choosing the cartoons, but I never allowed him to try. It was the only disagreement we ever had.

What sort of stories would Puzo write for you?

You name it—war, women, desert islands, a few mini-Godfathers. At one point we ran out of World War II battles; how many times can you storm Anzio, Italy? So we had to make up a few battles. Puzo wrote one story, about a mythical battle, that drew piles of mail telling him he had misidentified a tank tread—but no one questioned the fictional battle itself.

There has never been a more natural storyteller. I suppose it was mildly sadistic of me, but I would show him an illustration for a thirty-thousand-word story that had to be written that night. He’d get a little green around the gills, but he’d show up the next morning with the story in hand—a little choppy, but essentially wonderful. He wrote, literally, millions of words for the magazines. I became a hero to him when I faced down the publisher and got him $750 for a story—a hitherto unheard-of figure.

Do you think this experience later helped when he wrote The Godfather?

He claimed that it did. If you look at his first novel, The Dark Arena [1955], you’ll see that the ability is there, but there is little in the way of forward motion. He said more than once that he began to learn about the elements of storytelling and narrative at our company.

I can’t resist telling you this: In l963, Mario approached me and somewhat sheepishly said he was moonlighting on a novel, and he wanted to try out the title. He said, “I want to call it The Godfather. What do you think?”

I told him that it didn’t do much for me. “Sounds domestic. Who cares? If I were you, I’d take another shot at it.”

A look of steel came over his face. He walked off without saying a word. He was usually mild-mannered, but the look was terrifying. Years later, he always denied being “connected,” but anyone who saw that look would have to wonder. The thing is, I was right about the title. It would have been a poor choice for any book other than The Godfather.

In the mid-sixties, after the sale of the book, I heard him on the phone to his publisher, asking for more money. They said, “Mario, we just gave you two hundred thousand dollars.” He said, “Two-hundred grand doesn’t last forever.”

Wonderful man—perhaps not the most intelligent person I’ve known, but surely the wisest. On one occasion, he saved my life.

How so?

I became friendly with the mobster “Crazy” Joe Gallo when he was released from prison in l971. The actor Jerry Orbach, who starred [in 1967] in one of my plays, Scuba Duba, was also a pal of Joey’s.

Joey had a lot of writer friends—he had read a lot in prison. He loved [Jean-Paul] Satre, but hated [Albert] Camus, whom he called a “pussy.” When he was released, there were about fifty contracts out on his life. He was trying to soften his image by hanging around artistic types. His “family” would hold weekly Sunday-night parties at the Orbach’s town house in Chelsea. I attended a few of these soirees, and I noticed that every twenty minutes or so Joey would go over to the window, pull back the drapes a bit, and peer outside.

I told Mario that I was attending these parties, and that I wanted to bring my wife and sons along. The food was great—Cuban cigars, everything quite lavish. The actor Ben Gazzara [Husbands] usually showed up, as did Neil Simon, and a great many luminaries. Mario considered what I told him and said, “What you are doing is not intelligent.” And that was it. I was invited to join Joey and a group at Umbertos Clam House the very night [April 7, 1972] he was gunned down. Mario played a part in my saying I had a previous engagement.

What was Mario’s reaction to the third Godfather installment?

I don’t recall him being awed by any of the installments. What impressed him was the great cascade of money that came pouring in.

If he was upset about anything, it was that Hollywood never asked him to write comedies. He once told me, “They,” meaning Hollywood, “never call me for comedy.”

Let’s talk about the characters that you tend to create: They are often very likable, even when they shouldn’t be. One character, Harry Towns, who’s been featured in numerous short stories and in two novels since the early 1970s, is a failed screenwriter and father. He’s a drug addict who snorts coke the very day his mother dies. He sleeps with hookers. He takes his son to Las Vegas and basically forgets about him; he’s much more concerned about his own body lice. And yet, in the end, Harry Town remains very funny and likable.

The late Bill Styron [author of Lay Down in Darkess and Sophie’s Choice] paid me a compliment that I treasure. He said, “All of your work has great humanity.” Maybe he said that to all of his contemporaries, but he seemed to mean it. I tried to make the character of Harry—for all of his flaws—screamingly and hurtfully honest, and that may have provided some of whatever appeal he has. I’m a little smarter than Harry; he’s a bit more reckless than I am.

I have about a dozen voices that I can write—my Candide voice, the Noël Coward voice—but I keep coming back to Harry.

One Harry Towns story, “Just Back from the Coast,” ends with Harry watching the NASA moon landing in his ex-wife’s house, with her overseas and his child off at summer camp.* He’s alone. Your characters, including Harry, tend to be very lonely, but your life seems like it was anything but.

I’m not sure what other lives are like—but one of my favorite words is adventure. With that said, for a Jewish guy an adventure can be a visit to a strange delicatessen. I have plenty of friends, acquaintances, family, but much of the time I enjoy my own company. Most of writing is thinking, and you can’t do much of it in a crowd. Whenever I used to duck out on a dinner with “the guys,” Mario would defend me by saying, “Bruce is a loner.”

* “. . . . Where were the Puerto Rican astronauts? Where were the black ones? He couldn’t recall seeing any spacemen of the Hebraic persusasion running around either. But then again, Towns remembered pictures of the pinched and weary faces of some of the astronauts’ wives and it became his guess that all wasn’t as tidy as it came off in the national magazines. He knew that those long separations for work did marriages. There was probably no beating the system even if you were a non-ethnic space pioneer and your wife was an astronautical winner. He decided they were men, too, some good, some not so hot. They had experienced failure, ate too much marinara sauce on occasion, vomited appropriatedly, lusted after models, worried about being gay, about having cancer, even had an over-quick ejaculation or two. These thoughts comforted Harry Towns somewhat as he sat down on his boy’s bed, gave the TV set a few shots to get it started, and prepared to watch the fulfillment of man’s most ancient dream.”

“Just Back from the Coast,” Harper’s, by Bruce Jay Friedman, March 1970

Can the following be verified? That in the 1970s, you were the one-armed push-up champ at Elaine’s, the Upper East Side New York restaurant that was a gathering place for writers?

Yes.

How many did you do?

Who knows? I was probably too loaded to count.

Were you surrounded by a crowd of famous authors, cheering you on? Was Woody anxious to compete?

Not really. But we would have various athletic contests, generally beginning at four in the morning. There were sprints down Second Avenue, for example. It got more macho as the evening progressed.

I remember [the film director and screenwriter] James Toback trying to perform some push-ups and running out of steam. The restaurant’s owner, Elaine Kaufman, said, “Put a broad under him.”

Is it true that, in the late sixties, you a fistfight with Norman Mailer?

Yes, at a party he was holding at his town house in Brooklyn Heights. Mailer was looking for a fight. Instead of getting mad, I patted him on his head and said, “Now, now, Norman. Let’s behave.” We made our way to the street, and a crowd formed. We circled each other and we tussled a bit. Eventually he dropped to the ground. I helped him up and he embraced me—it was only a little later that I noticed that he had bit me. I saw the bite marks once I got home. I rushed to the hospital for a tetanus shot. I was afraid I was going to begin to froth at the mouth.

Let’s talk about Hollywood.

Must we?

For someone who has a good amount of experience as a screenwriter—you’ve worked on numerous screenplays over the years, including Stir Crazy and Splash—you seem to have a healthy attitude toward the film industry.

I don’t know of anyone who ever had more fun out there than I did. The work was not especially appealing, but I did have a great time. In fact, I would get offended when I was interrupted on the tennis court and asked to do some work. I thought Hollywood was supposed to be about room service and pretty girls, orange juice and champagne. When I was gently asked to write a few scenes, I was annoyed.

I did my work in Hollywood with professionalism and never took any money I hadn’t earned. But I could never tap into the same source I did when I wrote my books and stories—or plays, for that matter. Perhaps if I’d had some hunger to make movies at an earlier time I could have learned the camera, studied the machinery of moviemaking, and it would have been different. But for me, the gods at the time were Hemingway and Fitzgerald and Faulkner; there were girls in the Village who wouldn’t sleep with you if you had anything to do with movies: “You’d actually sell your book to the movies?” This was spoken with horror.

Shortly after I arrived in Hollywood, Joe Levine, the producer of The Graduate, summoned me to his office. He was a fan of my play “Scuba Duba.” He said, “You will never again have to worry about money.” When I left the office, I felt great. I’d never have to worry again about money! But he was wrong. Never a day passed that I didn’t worry about money. Later, I met Joe at the Beverly Hills Hotel and I reminded him of his prediction. He waved it off and said, “Oh well, you have so much of it anyway.” Not the rapier-like response I’d hoped for.

Screenwriting is the only writing form in which the work is being shot down, so to speak, as you’re writing. It’s always going to be, “Fine, now call in the next hack.” If someone were to submit the shooting script of [1950s’] All About Eve—updated, of course—it would only be considered a first draft. And a parade of writers would be called in to improve it. Hollywood doesn’t want a singular, unique voice. If F. Scott Fitzgerald, over the course of his career, could only earn one-third of a screenplay credit [on 1938’s Three Comrades] than what does that tell you?

Or Joseph Heller in Hollywood.

Right. He was there for years, but only had partial credits on two movies [1964’s Sex and the Single Girl, 1970’s Dirty Dingus Magee], and on a few episodes of the [early 1960s] TV show McHale’s Navy.

There’s an old-fashioned phrase—“pride of authorship”—that I never felt on the West Coast. I’m sure Woody Allen feels it, and maybe only a few others. Still, for a time, I was delighted as a screenwriter to be a well-paid busboy. And, oh, those good times!

Anything you care to tell me about?

I played tennis on a court alongside the actor Anthony Quinn. Back then, I was actually told that I resembled him. He kept glancing over at me. We both had shaky backhands.

I collided with Steve McQueen in the lobby of the Beverly Hills Hotel. A hair dryer fell out of my suitcase. Needless to say, it was embarrassing to have McQueen know that I used one.

And I spent one summer as a “sidekick” of Warren Beatty’s. My main function was to console his army of rejected girlfriends.

How did you even come to know Warren Beatty?

He loved Stern, and he was convinced he could play the central role in the film. I had to explain, patiently, that it was a bit of a reach. He was no schlub.

We would go to the clubs in L.A., including a place called the Candy Store. I never saw anyone who could bowl over women the way he could. He was a sweet, charming man—gorgeous, of course—and he made you feel that you were the only one in the world that he cared about. I don’t mean to be a tease, but there were a few episodes I’d be uncomfortable mentioning—especially now that he’s a family man with all those kids. Maybe if we have a drink sometime.

Hollywood is something. The name-dropping that goes on there is incredible. I had a friend who was an actor, and he called me one day. I could tell he had a cough. When I asked if he was okay, he told me that he had caught Pierce Brosnan’s cold. Another time, while I was on a movie set, a guy offered me a cigar and bragged that he had gotten it from someone who was close to Cher.

Were you happy with the first version of The Heartbreak Kid, which was released in l972? It was based on your l966 story for Esquire, “A Change of Plan.”

I thought the first version was wonderful. I’m permitted to say that because I didn’t write the screenplay—Neil Simon did. It actually sounded like something I might have written. Simon said that in writing it, he pretended he was me—although we’d never met.

What did you think of the 2007 remake, starring Ben Stiller?

I thought the first part—the revelation about the wife—was hysterically funny. The rest, for me, fell off a cliff. There are five screenwriters listed in the credits, along with the Farrelly brothers. And Lord knows how many uncredited screenwriters. The budget was north of $60 million. You would have thought that a simple phone call to the fellow who invented the wheel would have been useful. Maybe I know something. Maybe Neil Simon does. I would have helped out pro bono. But it would never have occurred to someone to make that phone call. I’m not upset about this. Just curious … amused.

I read a story about you that I assume cannot be true; that actress Natalie Wood once worked as your secretary.

No, that’s true. It was either my first or second trip to Hollywood. I was working on the movie version for the Broadway play The Owl and the Pussycat, and I needed a secretary. Or, at the very least, it was assumed I needed one.

The producer Ray Stark [The Sunshine Boys, Smokey and the Bandit] said, “I’ll find you a good one. Don’t worry.” I went over to his beach house and there, sitting by the pool, was Natalie Wood. Stark said, “Here is your new secretary.”

As a joke?

I said, “That’s very amusing, Ray. But this is Natalie Wood, from Splendor in the Grass, West Side Story, Rebel Without a Cause. Every boy’s fantasy.”

She looked up and said, “No, I really am your secretary.”

She was between marriages to Robert Wagner and seemed dispirited. I don’t think she was being offered major roles, and a shrink might have suggested that she try something different. This is self-serving, but I’d seen her at a party the night before and we had maybe exchanged glances. Who knows, maybe she liked me. What’s the lyric—I can dream, can’t I? In any case, she was my secretary for about a week.

Each morning, I’d pick her up in Malibu and drive her back to the Beverly Hills Hotel, all the while thinking, I’m sitting here with Natalie fucking Wood—and she’s my secretary. It was difficult staying on the highway.

Can you imagine a Hollywood actress doing that these days?

Unlikely.

What other Hollywood projects were you working on at the time?

I went out to California to work on The Lenny Bruce Story. Lenny had died a few years earlier. The executives wanted a writer who was crazy and strange, but also wore a suit. They wanted someone who would be presentable at a meeting—I was that guy. But I never worked on the project.

Why?

I had never seen Lenny Bruce, but I knew of his legend. I really wasn’t interested in that type of work, actually. I just didn’t know enough about him to be a fan or to not be a fan.

I once heard of a woman at one of Bruce’s performances who stood up in the middle of the act and started screaming, “Dirty mouth! Dirty mouth!” I wanted that to be the title of the film—“Dirty Mouth!”, but I didn’t realize back then that I, as a screenwriter, was nothing more than a busboy. It was just a different world than what I was familiar with. The most important thing back then was to be a novelist. Now it’s the opposite.

You left the Lenny Bruce project?

I did, yes. But only after a truck pulled up to where I was staying, with men hauling boxes and files and every scrap of paper related to Lenny Bruce’s life—every letter, every deposition, every piece of correspondence. I remember that I hurt my leg carrying some of these boxes up to the attic.

I just got smothered with it all, and I ended up not doing it.

I don’t think I’ve ever discussed this before, but I found aspects of his life troubling. It made me uncomfortable. There were some similarities of his life that brushed up against mine. I was having domestic problems of my own, and the whole story made me uncomfortable.

Plus, I didn’t want to be the one to fuck up the Lenny Bruce story. I knew about his legend, even though I never saw him perform, and I knew how important he was to many people.

There was one piece in particular of Bruce’s that I thought was absolutely brilliant. It runs a little over 20 minutes and it’s called “The Palladium.” I think it’s one of the best twenty minutes of comedy ever.

My friend Jacques Levy, who directed the stage production of Oh! Calcutta! and then later Bob Dylan’s Rolling Thunder Revue, once said that all contemporary comedy springs from that half-hour.

In what sense?

Bruce uses a few different voices throughout the piece, which I’ve often found myself slipping into while writing. It’s this “What are you nuts? What are you crazy?” type of attitude; it was a very modern sensibility when he performed it in the mid-sixties.

It’s about a minor Vegas comedian named Frank Dell who wants to perform in “classy rooms.” He just bought a new house with a pool and patio.* His manager gets him into the Palladium in London. He starts off with his bad schtick: “Well, good evening, ladies and gentlemen! You know, I just got back from a place in Nevada called Lost Wages. A funny thing about working Lost Wages . . . ” He’s bombs so badly that he starts to say anything to get a response: “Screw Ireland! Screw the Irish! The I.R.A. really bum-rapped ya.” He still bombs and causes a near riot.

* In the routine, Bruce describes the chracter’s new house in Sherman Oaks, California, as the following: “The pool isn’t in yet, but the patio’s dry.” The Rolling Stones’ Keith Richards, thirteen years later, used a slightly different version when writing the lyrics to 1981’s “Little T&A”: “The pool’s in, but the patio ain’t dry.”

What did you make of the Bob Fosse-directed movie Lenny when it was finally released in 1974, starring Dustin Hoffman in the title role?

I thought Hoffman was miscast. The movie just barely scratched the surface of that man’s life. The film didn’t work at all for me.

You’re credited with writing the screenplay to 1982’s Stir Crazy, starring Gene Wilder and Richard Pryor. Were you happy with the finished product?

I liked that movie very much; I just liked the way it worked out. I could recognize my voice every once in a while watching that movie.

The idea wasn’t mine—it was a producer’s named Hannah Weinstein, who told me about this phenomenon in Texas where prisoners staged a rodeo. That’s all I was given. I wrote the screenplay, and Hannah was able to cast Richard Pryor and Gene Wilder.

There was one instance where I wasn’t happy. At the last minute, another writer was brought in to punch up the script or to add some dialogue. I visited the set during the scene where Gene mounts a mechanical bull. He pats the bull and says, “Nice horsey” a couple of times.

Well, I don’t write “nice horsey.” I mean, it’s simply something that I would never write for a character. Bed wetters say “nice horsey,” but not my characters. I didn’t know the rules and I was a little offended, so I started to walk off the set. So Richard—someone I had never met before—came running over and said, “Gee, I never met a writer like you. Take the money; don’t take any shit.” He said, “I’ve got fifty in cash. I think I’ll get out of here, too.”

He then said, “You ever get high?”

I said, “Once, in the spring of ’63.” I was just teasing, but I was in good form. I said, “Jews rarely tend to become junkies. For one thing, they have to have eight hours of sleep. They have to read The New York Times in the morning. They need fresh orange juice. So, no, I’ve never gotten high.”

We walked into his trailer and, the second we did, I knew I wasn’t going to be comfortable. Everything was foreign to me: pipes and wickers and just crazy things. It was all new to me. If we lit a match, we were finished.

My one regret with Stir Crazy is that I didn’t do more with Richard’s character. I should have fleshed his character out more, and I didn’t. I feel bad about that. What’s interesting is that Richard treated every word you wrote as if it were scripture. Gene was looser. For Gene, the dialogue was just a starting point.

You knew Terry Southern, the screenwriter for Easy Rider, Casino Royale, and Dr. Strangelove, quite well, didn’t you?

We were good friends, particularly in his late years. At one time, there was talk of Terry writing the screenplay for my play “Scuba Duba.” Warner Brothers didn’t quite trust him and assigned a veteran screenwriter named Nunnally Johnson [The Man in the Gray Flannel Suit, The Three Faces of Even, The Dirty Dozen] to the product. It’s a very sad story. Johnson took me to lunch at 21. He was very charming, in the David Niven style, and really appealing, and he must have been in his early seventies.

He told me, “I’m not going to hurt your baby.”

I said, “Well, hurt it. Do whatever you want with it!”

During the course of lunch, he asked me if I had any discards or rough drafts from the play—was there any work I’d written but wound up not using? I said, “Sure, tons. But it’s not worth looking at.” He said, “Indulge me.”

Against my better judgment I showed him the material. The sad part is that when the screenplay was sent to me, a lot of this material was shoehorned into the film script.

I wasn’t the least bit offended or annoyed. I just felt so sad. He had reached a point in his career where he needed a job and was a little desperate. And he was one of the great screenwriters years before; he wrote over 25 movies.

Do you think Terry’s contribution was important to Dr. Strangelove? Terry co-wrote the script with Stanley Kubrick and Peter George, but Kubrick later claimed that Terry’s role wasn’t as significant as many people thought.

I would trust Terry’s account in this area. He was always collaborating and getting into awful squabbles about credits. He was a generous man and easily taken advantage of—picked apart, really—by the wolves.

How does a writer like Terry Southern age—where you always have to produce work that has the capacity to astonish?

Some keep it up. Some fade. Others simply push on. Churchill once said, “If you’re going through hell, keep going.” Terry had an especially tough time throughout the last decades. Had the culture changed? Was he out of sync? There is always that worry.

It’s a shame. He had the most unique voice of any writer I knew. He was a brave man in print, but vulnerable in life—no doubt a familiar story.

I once leased an apartment in New York that had an S&M guest room. Terry saw the black walls, the mirrored ceiling, the whips and chains stored in the closet. A room that had his name on it. He said, “Grand Guy Bruce, would you mind terribly if I crashed in here for a bit?” I said fine. It was three in the morning.

I then realized that painters were coming at around seven in the morning to ready the room for my young son Drew, who was moving in for awhile. They were going to re-paint the all-black walls.

One of the painters said, “We can’t work. There’s a man sleeping in that room.” I said, “Don’t worry about it. Just paint around him.” Terry fell asleep in this Marquis de Sade room, and woke up hours later with photos of Mickey Mantle on the walls. He didn’t say a word, just shook it off and went on his way.

You leased an apartment with an S&M room?

It was a lovely place, had a great terrace, lots of space. It just happened to have a guest room with all that bondage equipment.

What exactly was Terry doing in the room before he fell asleep?

He’d had a big night. Let’s put it that way.

Do you think Terry wasn’t respected in the latter part of his career because he wasn’t producing “quality lit”? Toward the end of his life, he was writing for National Lampoon and High Times.

Terry is the one who invented that phrase. He was an easygoing man, contented, amused by life. I don’t think he ever felt bitter or resentful with the way things turned out in his career. I know he had grave financial difficulties toward the end of his life—but he wasn’t a complainer.

He was respected throughout his life by the people who counted, so to speak. And there are all these new readers coming along. His books and films exist, ready to be enjoyed. His final words were, “What’s the delay?” I love that.

You’ve written eight novels and more than one-hundred short stories. After all these years, is writing still difficult for you?

Actually, I’ve written more than two-hundred short stories—half of them are languishing in an archive.

But God yes, writing is still difficult and always will be. I’m suspicious of writers who go whistling cheerfully to the computer.

Are there any writers’ tricks you’ve learned over the years that have made the process a bit easier?

Not really. I’m hesitant to begin a short story unless I know the last line, or a close approximation of it. I’m always apprehensive when I begin work each day. After a lifetime of this, I still can’t get it clear that the actual process of writing tends to erase the fear.

I’m not the first to point out how essential it is to, on occasion, discard a favorite passage in the interest of pushing on with a good story. Isaac Bashevis Singer said that the wastebasket is a writer’s best friend. He also said that a writer can produce ten fine novels, but it doesn’t mean that the next one will be any good. It mystifies me that after a lifetime of writing it would still be like this. I should be able to solve any problem—but it doesn’t work that way. Each story or book presents a new challenge. That’s probably a good thing, though. It keeps me on my toes.

I sometimes wonder if readers understand how difficult it is to write a short piece, be it a story or essay. Even though the story is smaller in scope, everything has to be pristine.

I don’t feel that a short story is necessarily smaller in scope than a novel. It’s not as if someone who runs the 100-yard dash is any less of an athlete than someone who runs a mile race. I read a short story by John O’Hara recently that has more dimension packed into its three pages than many novels.

In archery terms, you either hit the bull’s-eye in a short story or it fails. I sometimes think there’s an invisible fuse that runs through a good story and, at the end, it ignites. There is no margin for error. You can’t take time out to admire the scenery, as you can with a novel. Norman Mailer called the short story “the jeweler’s art,” which I think is apt.

The short story is the stepchild of American literature. Publishers—and many writers—think of it as a step in the direction of a novel, not an end in itself. Sort of like saying the runner who excels in the l00-yard dash isn’t much of an athlete.

One last point: I think many of our acclaimed novelists do their best work with the short story: Hemingway, Irwin Shaw, John Updike, Joyce Carol Oates. Then again, the time when a writer could make a living just writing short fiction and jouranlistic pieces is over.

Do you still write every day?

Yes—or at the very least, I worry about it.

I do some teaching, and I put the emphasis on focus, as well as the importance of making every sentence count. [Novelist] Francine Prose once quoted a friend as saying this requires “putting every word on trial for its life.” I believe this. You can read the entire works of a major writer and never find a bad—or unnecessary—sentence.

Do you have any specific instructions for those students who want to write stories with humor?

I’d suggest you stay away from irony or satire; there’s very little money in it. You’re likely to wind up with reviews—like some of mine—that say, “I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry.” There’s no such question in Dickens. Most readers would prefer to know exactly where they stand, where the author stands, and how to respond. Ergo, no irony permitted.

I’d advise students not to try to be funny. Nothing is more depressing than someone caught making such an effort. If a story or sketch is intrinsically funny, if it deserves to be funny, it will make people laugh. Truth—bitter and unadorned truth—is a good guideline.

Asking yourself “What if … ” is a good starting point for a story. What if I befriended a pimp and he asked a straight-laced character to watch over his stable of women while he was in prison? That later became a story for Esquire called “Detroit Abe.”

As for television writers, in comedy or drama, there’s a simple rule: Include the line “We have to talk,” even if your characters have done nothing but for half an hour. Producers love that line. Writers are brought in and paid a fortune for their ability—and willingness—to write that line.

I also like the writer Grace Paley’s single piece of advice: “Keep a low overhead.”